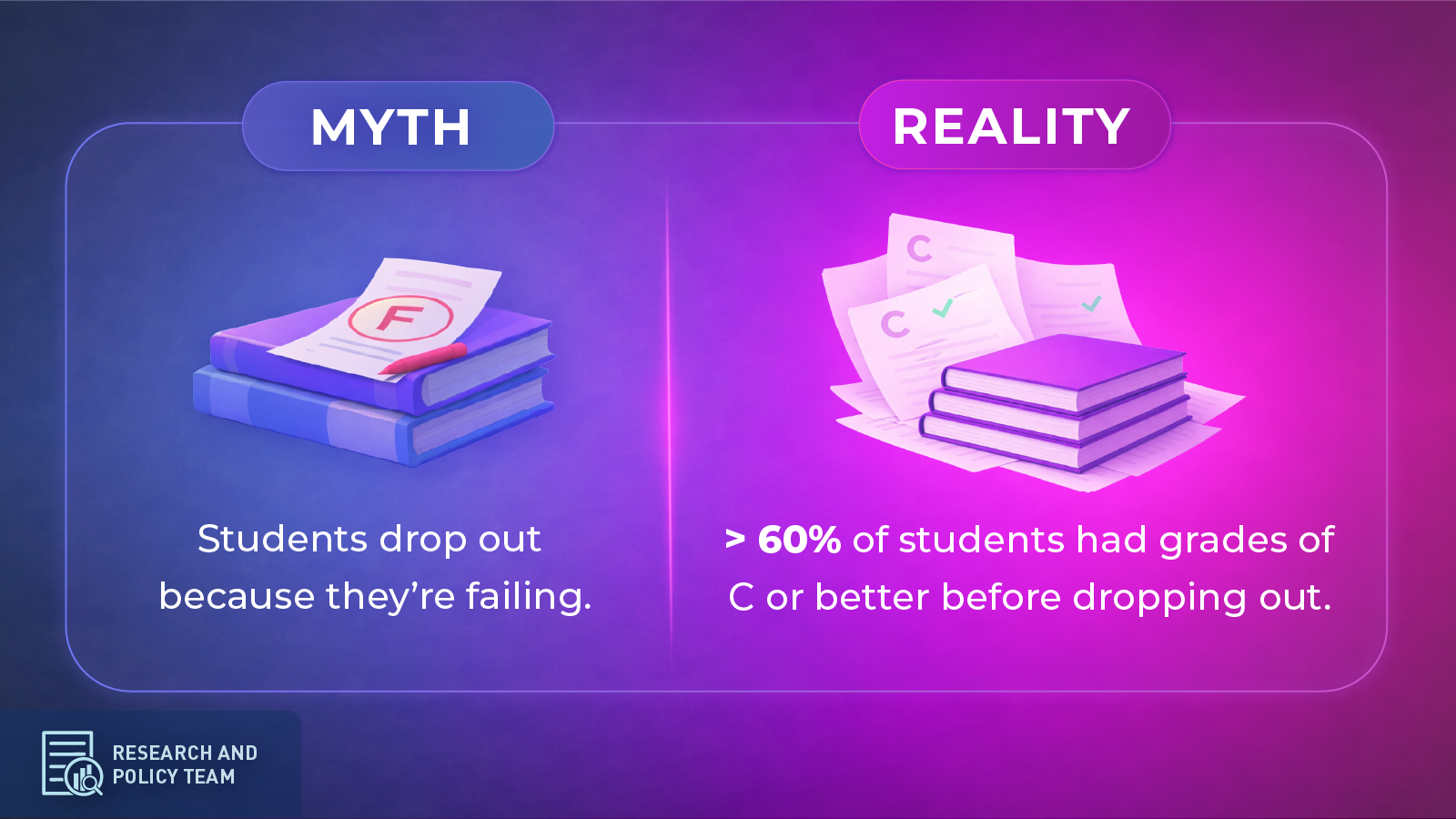

Here’s a statistic that should fundamentally change how we think about dropout prevention:

Over 60% of students who drop out had grades of C or better before leaving school.

Read that again. The majority of dropouts weren’t failing academically when they left. They were passing. Some were even doing well.

This contradicts everything most people assume about why students drop out. It’s not primarily about academic failure. It’s about something deeper and understanding that difference is critical to solving America’s dropout crisis.

The Engagement Crisis

When researchers survey students who left school, academic failure ranks surprisingly low on the list of reasons. Instead, the top factors are:

- 47% said classes were uninteresting or they didn’t see the relevance

- 69% weren’t motivated to work hard

- Many felt weak connections to teachers or peers

- 32% cited boredom as a major factor

Only about one-third said failing academically was a major reason for leaving. The problem isn’t that students can’t do the work — it’s that they don’t want to.

At Acceleration Academies, we hear this constantly from students we re-engage:

- “I just didn’t care anymore.”

- “Nobody noticed when I stopped showing up.”

- “I couldn’t see the point.”

These aren’t lazy students or lost causes. They’re young people who felt disconnected from an experience that wasn’t designed for them.

The Disengagement-to-Dropout Pipeline

Dropout isn’t a moment, it’s a process. Students don’t suddenly leave. They disengage gradually, often over years:

Early warning signs appear:

- Chronic absenteeism (missing 10% or more of school days)

- Grade retention (being held back)

- Declining GPA

- Disciplinary incidents

- Course failures in core subjects

Disconnection deepens:

- Weak relationships with adults in the building

- Feelings of not belonging

- Perception that “school isn’t for people like me”

- Loss of hope about future opportunities

External pressures mount:

- Family economic stress

- Caregiving responsibilities

- Work obligations

- Housing instability

- Justice system involvement

By the time a student officially drops out, they’ve often been psychologically gone for months or years. The formal withdrawal is just making official what’s already happened.

What the Pandemic Revealed

COVID-19 exposed how fragile student engagement really is. When the physical connection to school buildings disappeared, thousands of students simply vanished.

In surveys since the pandemic, students commonly mention:

- Feeling isolated and disconnected

- Mental health struggles (anxiety, depression)

- Falling so far behind it felt impossible to catch up

- Losing motivation in remote learning environments

Even after returning to in-person schooling, many students never fully came back. They attend sporadically. They’re physically present but mentally elsewhere. They’ve given up.

The message is clear: when students lose connection to school, they leave. And engagement is fragile: it requires constant cultivation, not assumptions that it’ll persist automatically.

The Life Factors Schools Ignore

Academic struggle is often a symptom of deeper challenges:

The teen parent: Misses school for prenatal appointments, gives birth, returns exhausted from sleepless nights caring for an infant, falls behind, feels embarrassed, stops coming.

The working student: Takes 30-hour-per-week job to help family pay rent, can’t stay awake in class, misses homework deadlines, fails courses, calculates that GED-plus-immediate-full-time-work is better than struggling through two more years of school.

The mobile student: Family evicted, moves to different district, new school won’t accept all previous credits, now even further behind, doesn’t know anyone, figures “why bother?”

The student with unaddressed trauma: Experienced abuse, witnessed violence, dealing with PTSD, can’t concentrate, acts out, gets suspended repeatedly, eventually stops trying.

The student caring for family: Parent is ill, younger siblings need supervision, student must be home, attendance becomes impossible, academic failure follows, dropout seems inevitable.

Traditional high schools have no good answers for these situations. The rigid structure — seat time requirements, age-grade alignment, sequential coursework, 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. schedules — works beautifully for students whose lives fit the model. For everyone else, it’s an obstacle course designed to produce failure.

The Mental Health Dimension

Since COVID, mental health has emerged as a dominant theme in dropout conversations.

Students struggling with anxiety or depression describe school as overwhelming — too many people, too much noise, too much pressure, too little support. The formal dropout often comes after a period of increasing absence driven by mental health crises.

But here’s the thing: mental health challenges don’t exist in isolation. They’re often intertwined with the other factors: poverty, trauma, family instability. A student dealing with housing insecurity is more likely to experience anxiety. A student who experienced violence is more likely to struggle with depression.

Schools that treat mental health as separate from academic and social support miss the point. These challenges are interconnected, and effective intervention requires addressing the whole student.

What Actually Works

At Acceleration Academies, we’ve learned that re-engagement requires meeting students where they are, literally and figuratively.

Flexibility: Schedules that work around jobs, childcare, and family obligations. Evening classes. Self-paced coursework. Year-round enrollment.

Relationships: Small environments where adults actually know students. Advisors who check in regularly. Teachers who notice when someone’s struggling.

Relevance: Helping students see how education connects to their goals. Career pathways. Real-world applications. Choice in what they learn.

Supports: Case managers addressing barriers. Mental health counseling. Transportation assistance. Childcare support. Food security help.

Respect: Treating students as adults with agency. Acknowledging their challenges without lowering expectations. Believing in them when they don’t believe in themselves.

When we provide these elements, students who were “done with school” come back, persist, and graduate.

Rethinking Prevention

If most students drop out despite passing grades, then traditional prevention strategies are targeting the wrong thing.

We don’t primarily need more tutoring (though that helps). We need more engagement strategies. We don’t need stricter attendance policies. We need stronger relationships. We don’t need harder tests. We need more relevance.

And critically, we need flexibility. The four-year, seat-time-based, age-graded model is the problem for many students, not the solution. Insisting everyone fit that mold guarantees continued high dropout rates for vulnerable populations.

The Bottom Line

Students don’t leave school because they’re incapable. They leave because school isn’t working for them, and often, they’re right. The system is rigid. The structure doesn’t accommodate their realities. The content feels irrelevant. The relationships are weak or absent.

These are solvable problems. But solving them requires acknowledging that one-size-fits-all schooling will always produce dropouts among students whose sizes don’t fit.

The question is whether we’re willing to build systems designed for all students. not just those whose lives conform to traditional expectations.

This is the second part in a series exploring the economic and social benefits of re-engaging high school dropouts.

The Acceleration Academies’ Research & Policy Team is dedicated to advancing data-driven insights that help schools and communities better support opportunity for youth. Our team focuses on shining a light on barriers faced by students who have been disengaged from traditional high school pathways, elevating actionable data that helps schools re-engage learners, and driving evidence-based solutions for students who have been left behind.