As she travels around Martin County, Jeannette Navarro regularly encounters young people who remind her of her childhood self — recently arrived immigrants from Latin America who are striving to learn English and find success in school.

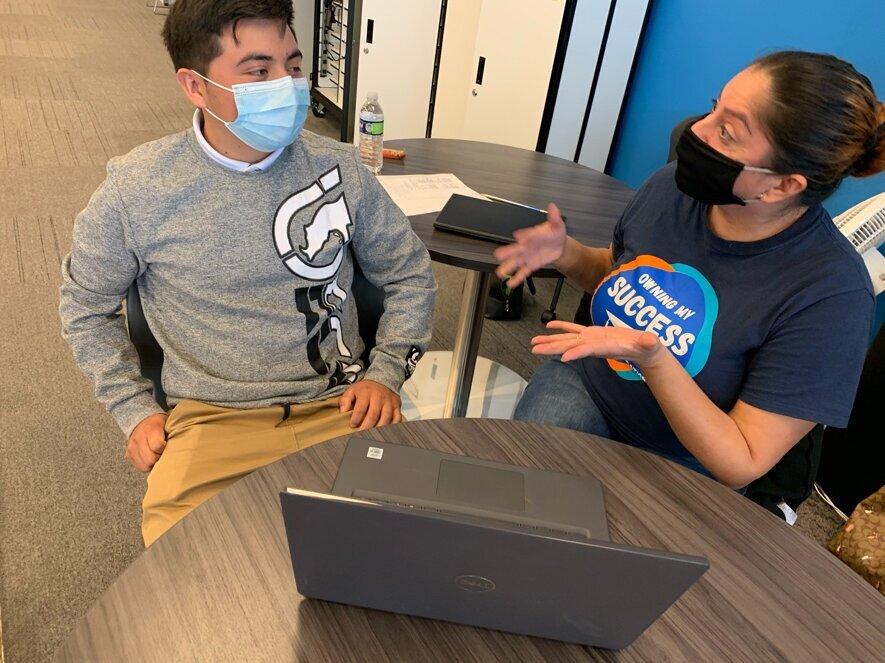

“I know how hard it is, because I came here when I was seven years old,” says Navarro, who spent her early years in El Salvador and now works as a graduation candidate advocate at Martin County Acceleration Academy.

One thing has changed since Navarro was a child: since opening in January 2019, MCAA has offered students learning English as their second or third language the chance to work at an individualized pace with caring educators in an uncrowded environment.

Many of the students who come to MCAA have come from Guatemala, where drug cartel violence made them and their families too frightened to stay. Arriving in Florida, they enrolled in traditional high schools but sometimes found it hard to keep up.

“It was very difficult because they put me in a class with everybody speaking English and nobody spoke my language,” says Marvin Lopez, 19.

“Imagine sitting in a classroom and having somebody speaking gibberish. That’s what they hear — gibberish,” says Navarro. “It’s overwhelming.”

The Martin County School District provides many services to English language learners, but some students benefit from a more individualized approach, a flexible schedule and a school where students over 18 don’t feel out of place. Working in partnership with the district, MCAA offers an alternative that can keep them on track to earn a diploma instead of becoming another dropout statistic.

Fredy Sucuc is another Guatemalan immigrant who’s found a home at MCAA. In addition to the language help they receive, Sucuc and many of his fellow New Americans need to work part- or full-time to support themselves and their families. They say the scheduling flexibility that is central to Acceleration Academy’s mission is a big help.

Fredy’s father is unable to work right now due to a medical issue, and the income the young man brings in is vital for his family, including his 7-year-old sister. Fredy, 19, works until late every day building walls for new homes.

Sometimes, he acknowledges, it’s tough to dive into coursework after a long day on the job site. “Sometimes when I come home extremely tired, I just want to eat and go to sleep,” he says. Still, he keeps at it. “I need to obtain my diploma.”

Navarro is there to provide encouragement that is firm but loving, say Fredy and his classmates. “She says, ‘You can do it, you can do it! ’”

The rural community of Indiantown has become a particular focal point. Census data shows that 62 percent of the community’s approximately 7,200 residents are Hispanic or Latino, including a growing community of Guatemalans. Most arrive speaking a dialect, and some have to learn Spanish as well as English to communicate in their new community and country.

They all arrive with dreams.

Marvin has three brothers and one sister, all younger than he. He works with his father as a plumber, and hopes to become a police officer after he graduates. With the region’s growing population of native Spanish speakers, he says, the police force needs more officers who can communicate clearly during stressful situations.

“There are lots of people who don’t speak English and they don’t understand” what officers are asking or telling them, says Marvin. He wants to be an honest, hard-working role model for his younger siblings.

“I want to prove to them that you can do it,” he says.

Fredy is also considering a career in police work, although construction remains a viable option. He also has a passion for music, he says with a shy grin. “I play saxophone and trumpet and piano” at Holy Cross Catholic Church in Indiantown, and might like to perform more widely.

Asked for words he’d offer his stepsister and others who might follow in his footsteps, he says this: “Anything’s possible if you just believe in yourself.”